| Forbes Field, the

home of the Pittsburgh Pirates, was constructed in 1909 and used until 1970.

I’ve attended

many major league baseball games and followed the Pittsburgh Pirates

baseball team since I was in 3rd Grade way back in 1947. Suddenly, I’m realizing I’m an old timer now. Kids read about how it was; we lived it. So I’ll share what I remember from my youth.

It

was all day games until 1944 when games first were under the lights. There were

night games usually on Tuesdays and Fridays. Game time was 8:30 pm since streets were still relatively safe at night. Day games were the norm otherwise. Wrigley Field, the home of the Chicago Cubs, didn’t even have lights until the 1990s.

There were only 16 major league

teams, no further west than St. Louis. The older

National League had the Boston Braves, Brooklyn Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, Cincinnati Reds (the oldest team), New York Giants, Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburgh Pirates, and the St. Louis Cardinals. The American League teams included the Boston Red Sox, Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, Detroit Tigers, New York Yankees, Philadelphia Athletics, St. Louis Browns (today the Baltimore Orioles), and the Washington Senators (“First in war; first in peace ; and last in the American League” moved to Minneapolis).

Atlanta,

Baltimore, Dallas, Denver, Houston, Kansas City, Los Angeles,

Miami, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Oakland, Phoenix, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and Tampa Bay only had minor league franchises which were supplied by major league teams as part of their farm systems. Los Angeles and San Francisco were farm teams (Pacific Coast League) of major league clubs until 1958 when Horace Stoneham of the New York Giants and Walter O’Malley of the Brooklyn Dodgers agreed to move west together. New York was then suddenly left with only one major league team. It devastated the people of the New York City Borough of Brooklyn since they identified so closely with the team.

Since

teams traveled by train, they would have several two or three week home

stands for their 77 home games……11 games with each team. They would travel for two or three weeks at a time for their 77 away games. To play the 154 game season, there would be four games on the week-end with a double header on Sunday. Saturday was a day game to rest the players for the Sunday double header. Monday was a day off or travel day. Thursday was for a day game so that they could travel all night on a sleeper train to their next destination and get ready during the day for the Friday night game in the next city. The players would spend the travel time reading, but mostly playing cards. By the 1960s air travel was the standard mode of travel.

National

League and American League teams played each other only during

the World Series and Spring Training. Legendary were the Subway World Series games between the dominant New York Yankees and the New York Giants or the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Radio and Television. KDKA Pittsburgh was one of the first to

broadcast

games in the late 1920s. Home games were broadcast live. The radio announcers would broadcast away games from the studio while receiving play by play accounts by ticker tape which was also used for stock market quotes. Broadcasting the games live on phone lines were just too expensive. The announcers would then act like they were at the game, giving it life and often improvising descriptions.

Rosey

Rosewell and Bob Prince were very colorful

homer radio announcers. Rosey called a double a doozie maroonie. When

a Pirate would hit a home run, Rosey would exclaim: “You can raise the

window, Aunt Minnie; here it comes. He would use a whistle with a rising

pitch for the ball’s ascent and a descending pitch for the descent. Then

the radio audience would hear a crash as Rosey exclaimed: “She never made

it.” When the Pirates were losing badly, as was often the case, Rosey

would moan: “O my aching back!” Too bad that he did not live long enough

to see the 1960 Pirates World Series victors.

Forbes Field (see

photo at beginning of the article) was built in 1909 to replace Exposition Park,

at about the same time as Chicago’s Wrigley Field and Boston’s Fenway

Park. In 1970 Forbes Field was torn down

and replaced by the cookie cutter multi-purpose Three Rivers Stadium, almost

identical to stadiums in Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Philadelphia. In 2001 it was replaced by PNC Park, which

imitated Forbes Field to a large extent.

Outside are statues of greats, Honus Wagner, Roberto Clemente, and

Willie Stargell.

There

is a model of old Forbes Field built to scale as it looked in 1909 at the

Carnegie Science Museum in Pittsburgh amidst the model trains running about

model buildings typical of the 1920s in Western Pennsylvania. In 1925 the double deck Right Field Stands

were added. Hall of Famer Honus

Wagner played shortstop that year and was the third base coach for the

Pirates in the 1940s. Only three players

ever hit towering home runs that cleared the roof of the Right Field

Stands……..the incomparable Babe Ruth (his last home run), Ted Beard (I was there

for that one), and Willie Stargell.

The engineering of the time could not avoid many posts that supported the second tier of seats and the roof above. These posts obstructed the view of anyone sitting higher up in the stands. PNC Park avoids these posts with modern construction methods. However, the seats in front of the posts were very close to the field. In the left field corner pocket, only a few feet separated the bleachers from the foul pole.

A

brick wall covered with ivy traversed the outfield. There was no padding except the ivy to

protect outfielders crashing into the wall.

The furthest point from home plate was 450 feet as I recall. Beyond the wall were the trees of Schenley

Park and the Carnegie Library a few hundred feet away. In left field there was a manual scoreboard

big enough for a couple of men to enter and place the number of runs per inning

for up to eight games in both leagues.

Balls and strikes were shown with small but bright neon lights. Wrigley Field and Fenway Park still use the

same type of scoreboard. The ball had to

clear the scoreboard to be a home run. I saw many a game there through grade school, high school and college even though the Pirates had some terrible years. Watching Ralph Kiner threaten Babe Ruth's record in the late 1940s were exciting. Even though I was still in grade school, my parents let me go to the games. It was easy to pick up a street car (trolly) less than two blocks from our home. It let us off on 5th Avenue a half hour later in Oakland just two blocks from Forbes Field on 5th Avenue. I saw many games free since kids less than 12 years of age were let in free on Saturday afternoon games which were standard. Thursday was get away day to take the train to the next destination and thus was an afternoon game for Ladies Day.......only 50 cents. In 1968-1969 I was working on my Master's Degree in Business at Pitt and lived in a dorm (418 Tower C) across the street. While studying, I followed the game on the radio and would take a break and watch the 7th, 8th, and 9th innings free since the gate keepers left their posts by then. It was fun watching Roberto Clemente make his basket catches. We would sit in the left field bleachers and pay $1.00 for a seat including double headers. When the Pirates acquired slugger Hank

Greenberg from the Detroit Tigers at the end of his career in 1947 the

bullpens were placed in front of the walls to shorten the field by 30 feet to 330

feet down the line to make it easier for him and his protégé Ralph

Kiner to hit home runs. Thus the

bullpens were named the “Greenberg Gardens”. With apparently no real power hitters left, Branch

Rickey had it removed in 1954. However,

he overlooked a rookie, Frank Thomas, who later pleaded for the restoration of the

Greenberg Gardens. He was to hit 286

home runs. Ralph Kiner hit 369 in his

career.

Most visiting teams stayed at the Schenley Hotel a block away. Today it is the Student Union of the University of Pittsburgh. It was a thrill for me to watch visiting stars such as Stan Musial (ethnic Polish), Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Hank Sauer, Johnny Mize, Hank Aaron, Eddie Matthews, etc. About two blocks away is the Cathedral of Learning, built in 1933, probably the tallest university building in the world......33 stories. I got my MBA on the 19th floor in 1969 and lived on campus. Thus I would listen to the game on the radio and then take in the last two innings when the ticket takers would abandon their posts at the gates. In the photo above the large building in the background is the Carnegie Library, Museum of Natural History, and the Museum of Art…….all in one building.

Forbes

Field was also used for Pittsburgh Steeler and Carnegie Tech football games

when it played and beat the likes of Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame and other Division

1 powers.

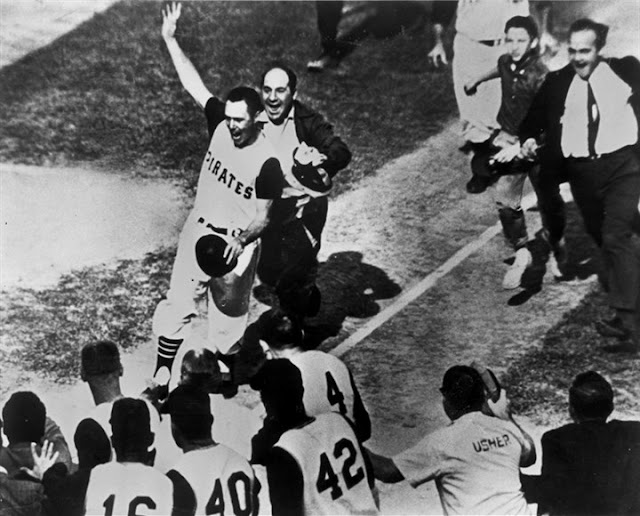

The most memorable World Series game ever was played at Forbes Field in 1960. Bill Mazeroski, primarily known for his great fielding at 2nd Base, hit his dramatic home run over the left center field wall (405 ft.) to win the 7th Game of the World Series against the New York Yankees in the 9th inning. The games the underdog Pirates lost were blowouts (16 - 3; 10 – 0; 12 – 0); their wins were close (6 - 4; 3 – 2; 5 – 2; 10 – 9). Vernon Law won two of those games and Harvey Haddix the other two. The dominant Whitey Ford pitched both shutouts for the Yankees. If Casey Stengel had started Whitey Ford in the first game instead of the third game, he might have pitched in three games and the Pirates World Series victory could have gone the other way. That Yankee team featured Hall of Famers Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Yogi Berra, etc. The part of the wall the home run cleared is kept intact today as a monument. For a very well written book, a sports classic that describes the background, the atmosphere, the color, managerial strategies, and the suspense of that epic 7th Game, read "THE BEST GAME EVER: Pirates vs Yankees October 13, 1960" by Jim Reisler and published by Carroll & Graf, 2007. For a great video of the last three innings of that epic game, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5MtnU4yno4o) and the dramatic home run click on. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FE1nYMg-jU4. For written summaries, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1960_World_Series and http://www.post-gazette.com/sports/2015/10/13/1960s-World-Series-Pirates-vs-Yankees-55-years-later/stories/201510130018. For the box scores, click on http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1960_WS.shtml. ESPN called it the greatest game ever played (http://www.espn.com/mlb/playoffs/2010/columns/story?id=5676003).

Bill

Mazeroski remains the only player to win Game 7 of the World Series with a

walk-off home run.

The

victory was so sweet because the Pirates had not won a pennant since 1927, a 33

year wait. That

was the last championship that a Pittsburgh professional sports team won at

home. The world series victories in 1971

and 1979 were in

Baltimore. The Pittsburgh Penguin hockey

championships were in Minnesota (1991), Chicago (1992), Detroit (2009), and San

Jose, California (2016). The Steelers,

of course, won their Super Bowls on neutral sites in the 1974, 1975, 1978, 1979,

2005, and 2008 seasons.

Danny

Murtaugh of the Pittsburgh Pirates and the great Casey Stengel of the New York

Yankees, the opposing managers in the

1960 World Series, greet each other.

Danny Murtaugh came out of retirement in 1970 and managed the 1971 World

Series champions before retiring again in 1976 due to same health issues. He has been a Hall of Fame candidate and

could make the Hall on the 50th anniversary of the 1971 World Series

victory.

Managers. Danny Murtaugh came to

the Pirates in 1948 in a trade. Playing

2nd Base he made an impact upon a perennial 2nd Division

team, batting .290 and helping the Pirates to be a pennant contender and

finishing in 4th place. His

playing days were over in 1953 and became a coach in the Pirate farm system,

particularly the New Orleans Pelicans.

In 1957 he took over for Bobby Bragan in August and led the team to play

.500 ball the rest of the way. The

following year the Pirates finished 2nd. In 1960 his Pirates had a magical season,

coming from behind to win many times.

In both of his managerial stints in the

late 1950s and 1970 he turned struggling teams around into winners and was

named Manager of the Year by the Associated Press and the Sporting News. In another magical season in 1971 for the first time ever

he fielded an all non-white starting lineup at one point……..a far cry from segregated

baseball up to 1947. Until that time the

major leagues had only all white teams and the blacks had their own leagues. In a quiet way he had a knack for leading and

handling people of different racial backgrounds and getting them to work

together.

Danny Murtaugh was a faithful

Catholic. Even on road trips he gave

Sunday Mass his top priority, encouraging his coaches to accompany him and made

sure that his kids received a Catholic education through college. He belonged to the Knights of Columbus (a 1958

charter member of Council 4518 near Pittsburgh) and spoke at KofC banquets. As a 4th Degree knight, he served

as part of an honor guard at funerals when able to. Danny spent two years in the war effort (1943-1945),

insisting on a combat assignment with the 97th Infantry when given

the opportunity to stay stateside and play for the U.S. Army baseball team. During the off season he was very active in

his community and was even fire chief for a while. Murtaugh would give fees received on the

banquet circuit to charity.

As a kid in 1950, I once played catch

with his son, Tim and Danny Sr. joined us while still the Pirate 2nd

baseman. It was in the back yard of the

house he rented for the summer in Wilkinsburg.

My cousin, Martha Foley Loya, baby sat for him as she did with Ernie

Bonham. For more detail on Danny

Murtaugh click on

For more detail on Ernie Bonham,

click on

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/bonhati01.shtml.

Pitching. Complete games by starting pitchers were common

despite the fact that they only had three days rest between starts instead of

today’s four. Thus a typical pitching

rotation had four players, not the five of today. On May 26, 1959 in Milwaukee Harvey

Haddix (http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/haddiha01.shtml) pitched a perfect

game for 12 innings until halted by an error and a walk. With two outs Joe Adcock hit a walk off

double for an unearned run in the 13th inning. Lew Burdette pitched 13 innings of shutout

ball while scattering 12 hits, all singles for the win. After the game, Burdette (career record 203 -

144 and said to have often used the illegal spit ball) congratulated Haddix

saying: “you pitched the greatest game that's ever been pitched in the history

of baseball”. I heard the game on the

radio while studying at Carnegie Tech, now Carnegie Mellon University.

No manager today would allow a pitcher to pitch more than nine innings and seldom more than 100 pitches. In those days they didn’t do pitch counts, but according to Western Union which telegraphed the play by play, it was 115 pitches for an average of 9 pitches per inning, remarkable efficiency (82 strikes and only 33 balls). The next year he won two games of the 1960 World Series (see http://www.baseball-almanac.com/boxscore/05261959.shtml and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqV_HNYQtbA). His lifetime record was 136 – 116. For a great story about that game click on http://www.post-gazette.com/sports/pirates/2009/05/24/In-1959-Harvey-Haddix-pitched-perhaps-the-best-game-ever-and-lost/stories/200905240102.

Harvey Haddix walks

to the dugout after losing perhaps the best game ever pitched, giving up an unearned run with one hit, a home run

for a 2-0 loss. Both pitchers must have

pitched 150 - 175 pitches each. Today

complete games with 120 pitches are rare.

No manager today would have left Harvey Haddix or Lew Burdette in that

long.

A

relief pitcher would pitch until he tired or became ineffective; they did not

keep track of pitch counts; set-up pitchers and closers were unheard of. The relief pitcher would stay in until he

became ineffective. Elroy Face (http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/facero01.shtml),

the great reliever, had 18 wins with only one loss in 1959. He would often come into the game in the 7th

inning. When the Pirates were behind, he

would stay in the game long enough for the team to rally or blow the save and

then regain the lead for the win. He is

the first pitcher to have three saves (a total of 7 1/3 innings) in the same world series (1960). However

in the crucial 7th game, Face blew a fourth save, giving up 4 runs

in 3.0 innings (box scores at http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1960_WS.shtml). Kent Tekulve did it again with three saves for

the Pirates in the 1979 World Series.

With fewer pitchers, games

would usually last about 2 ½ hours. If a

player got a sore arm, his career was often over. Tommy John surgery was not developed until

the 1990s or so. Pitchers seemed to be

more durable then. That is probably

because pitchers today pitch with higher velocity. Bob Feller and Satchel Paige went on and on

with great fast balls in the 1940s and 1950s.

Vernon

Law, the leading starter and Elroy Face, the great reliever

were

a great combination in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

My

first baseball hero was slugger Ralph Kiner. He hit 23 home runs in 1946, 51 in 1947, 40

in 1948, 54 in 1949, 47 in 1950, 42 in 1951, and 37 in 1952, leading the league

each year (a record and the majors in the last six years) before being traded

in 1953 to the Chicago Cubs. The

Greenberg Gardens were helpful, but many if not most of his home runs were line

drives well over the scoreboard. I saw

one or two Kiner home runs that kept rising as it cleared the scoreboard and

left the ball park.

He generated a lot of excitement in

Pittsburgh despite the terrible teams he played for. He may have hit many more home runs with top

players backing him up, not having lost two years in the military during World

War II Navy pilot flying antisubmarine missions, and 162 games of today. A back injury ended his career at the age of

32. I remember the 1947 season when he

hit 51 homeruns, hitting something like 17 in September alone, often two or

three home runs at a time, each time generating headlines in the early edition

of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette after a day game. The local ice cream shop in Duquesne had a

life size cardboard image of him batting; he endorsed Sealtest ice cream.

He even wrote a short

column for the Pittsburgh Press, called “Kiner’s Liners”. That probably prepared him for a second

career as a radio and television broadcaster with WOR and a post game program

called “Kiner’s Korner” for the New York Mets for 52 years and was elected to

the Hall of Fame. See

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Kiner

Frank Thomas

was another great slugger for the Pirates.

Between 1953 and 1958 he made major league baseball interesting in

Pittsburgh as the team’s slugger when they lost one game after another, hitting

as many as 35 home runs in 1958 and started the All Star game that year at

third Base. Had they not taken out the

Greenberg Gardens, Frank Thomas would have hit a lot more and gained the Hall

of Fame. In 1959 he left in a

blockbuster trade that gave the Pirates Smokey Burgess, Don Hoak, and Harvey Haddix……key

players that led the Pirates to the 1960 Pennant and World Series in 1960. Thomas played in the majors for 16 years,

hitting 286 home runs.

He’s now 87 years old as of 2016, living in Ross Township near Pittsburgh. Interesting is that he studied in the seminary for four and a half years before leaving. However, today his youngest son of eight children, Fr. Mark Thomas did finish the seminary and is pastor of Immaculate Heart Church in the Polish Hill section of Pittsburgh. It’s a good fit; his mother is ethnic Polish (Dolores Wozniak). See the article in the appendix on Frank Thomas below for more detail with photos and links to his stats.

Roberto Clemente came

up in 1955. He is probably the best all

around player the Pirates ever had.

Besides having 3000 hits, he had a legendary arm and was a tremendous

right fielder. I saw him take a ball off

the right field wall and then throw it like a rifle shot four or five feet off

the ground to home plate on one bounce to throw out a runner. He made the National League All Star Team no less than 15 times and got his 3000th hit in the last

game of the season in 1972.

As

his career moved forward, Roberto saw something bigger than baseball…….helping

others; He got more and more involved in the community.

His legacy includes a sports complex which he had built in Puerto Rico

to teach the game of baseball to kids.

Is A few months later in January 1974 he went on a mercy mission to help

earthquake victims in Nicaragua. On the

way his overloaded plane with a history of problems went down into the ocean.

Andrew McCutchen receives the 2015 Roberto Clemente Award. He is flanked by Vera Clemente and one of her sons.

He was inducted into the Hall of Fame within months after his death without the mandatory wait of five years; the only other was Lou Gehrig. The Right Field wall at PNC Park is named the Clemente Wall and is exactly 21 feet high, corresponding to the number he carried on his uniform. His statue appears outside of PNC Park along with Honus Wagner, and Willy Stargell. For more detail go to

The

Pirates had many great teams and many awful teams from 1946 - 1960. Probably the worst of them all was the 1952

team which the Press nicknamed, the “Rickey Dinks” in mocking the youth

movement of Branch Rickey. He did,

however, lay the ground work, and Joe L. Brown continued the job of producing a

pennant contender by the end of the decade.

That team won only 42 games and lost 112 with only a 154 game

schedule. Murry Dickson, an

excellent veteran pitcher, had a 14 - 20 record that year. Branch Rickey told Ralph Kiner, who demanded

a raise in 1953: “We finished last with you and we can finish last without

you”. He was traded that year to the

Chicago Cubs. The O’Brien twins formed a

double play combination at shortstop and second.

In

late May 1956 Dale Long (http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/longda02.shtml)

hit a home run in eight consecutive games and the Pirates were riding

high. After peaking with a 30 – 20

record and in 1st place, they collapsed……losing something like 30 of

their next 40 games for another losing season.

As

in St. Louis and Brooklyn, the youth movement eventually paid off for Branch

Ricky; the Pirates became very respectable by 1958 under Joe L. Brown and the

Pirates won it all in 1960.

Dick

Groat from nearby Swissvale was an All American

basketball player at Duke, but became an All Star shortstop for the Pirates and

MVP in 1960, a

great shortstop with a .325 batting average that year.(See

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/g/groatdi01.shtml,

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/5f9f3329).

He was a rare two sport athlete, a star in Division 1 college basketball

and baseball. Branch Rickey offered him

a contract after his junior year in 1951.

Feeling a moral commitment to honor his four year scholarship in

basketball at Duke, Groat refused. Isn’t that an

example for today’s one year and done college basketball stars? However, the next year Dick Groat signed for

a $35,000 bonus and bypassing the minor leagues completely, he was the Pirate

starting shortstop on his second day in uniform in 1952, hitting .284 as a

rookie. Every morning he was tutored by

former Pirate Hall of Fame batting champion, Paul Waner at his batting range. That Fall Groat was the first draft choice

(third overall in the NBA) by the Ft. Wayne Pistons (today the Detroit Pistons. Then he was drafted by the Army and lost two

years at his prime. His number was the first retired at his alma mater Duke, the perennial college basketball power.

Bubble Gum Cards or Trading Cards (see

the one above on Vernon Law and Elroy Face).

As kids, we would buy bubble gum to get the cards of players. It was fun to collect and trade to obtain the

complete set. We would even gamble with

them, playing the game of toppers. Each

kid would flip a card onto the ground; the next kid would flip his card so that

it would land on one of the cards in the pot.

The successful player would take all of the cards on the ground.

Drugs. Performance enhancing drugs were unheard of,

but chewing tobacco and snuff were very common.

In the 1980s and 90s Lenny Dykstra was a great hitter, but also a poster

boy for losing much of his face because of cancer due to snuff.

The darkest aspect of

American sports history was racial segregation in all sports except

boxing and track. Blacks had to have

their own baseball teams and leagues…..the legendary Homestead Greys, Pittsburgh

Crawfords, Kansas City Monarchs, etc.

They developed legendary players that would have been without question,

superstars……..Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and many others. Rightfully so, many of them are today members

of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Branch Rickey (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Branch_Rickey,

http://baseballhall.org/hof/rickey-branch), General Manager of the

Brooklyn Dodgers brought in the great Jackie Robinson in 1947 to break the

color barrier amidst great resistance. The legendary Satchel Paige came in towards

the end of his career when well into his forties. In his prime he dominated major league

hitters in exhibition games. So many of

them would have been superstars, given the chance.

World War II. Most baseball players of the early 1940s traded their baseball uniforms for military uniforms to serve in World War II. After being the last player to bat .400 in 1941 served as a combat flyer and again over a year in the Korean War. Among the others who served were such Hall of Famers as Stan Musial, Ralph Kiner, Joe DiMaggio and many others. Imagine how may more records they could have broken were it not for their willingness to serve. In addition they played only 154 games, not 162 as today. During the war, the women’s league flourished and a one armed pitcher pitched for the St. Louis Browns.

The Business of Baseball

Salaries were modest and so were the admission

prices. The major league minimum salary

was $5000 per year and a super star as Ted Williams might make as much as $100,000. Paul Petit, a promising pitcher out of high

school, received a $100,000 bonus, but never did much in the major

leagues. It was a buck for a bleacher

seat and $1.40 for general admission. I saw two games of the 1960 World Series

in Yankee Stadium for only $3.00. Of

course, the dollar at the time went far. Peanuts went for a dime and a hot dog

for a quarter. The minimum wage by law

was $.75 per hour.

The Reserve Clause. Trades

were frequent. With the reserve clause in contracts, there was no such

thing as free agency; a player was stuck with a team as long as it wanted to

keep him. The player’s only recourse was to hold out (take it or

leave it), i.e., not play at all. If the player was indispensable,

the baseball club would eventually come to terms. Players were bought,

sold, and traded like commodities. When the great slugger Ralph Kiner

demanded more money, GM Branch Rickey replied: “We finished last with you and

we can finish last without you”. He was

traded a few months later. The article on

Frank Thomas from the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) (http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ff969dc6) in the appendix

below gives some remarkable

insights on how players were treated regarding salaries before free

agency.

With free agency it is difficult for a small market team to repeat a

world series victory, let alone build a dynasty since the team would be unable

to pay the higher salaries that their top stars would demand. Pirate fans had to wait 33 years for their

1960 pennant. It’s already longer than

that since the 1979 World Series Pirate victory. After the Pittsburgh Steelers won the Super Bowl a few months later, Pittsburgh called itself the "City of Champions" for a while.

A big positive was that superstars such as Stan Musial, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller, Warren Spahn, etc. would usually begin and end their careers with the same team. Thus people would identify the player with the team.

The Farm Systems. Players were developed on the playgrounds, on high school teams, and

with independent local teams, professional, semi-pro, and amateur. Without television, people would enjoy a

summer evening watching their local baseball team. They would sell a player’s contract when discovered

by a major league scout. I watched Wilkinsburg's sandlot team a number of times with my cousin Bob Foley. My home town of

about 17,000, one of many steel towns in the Monongahela River south of

Pittsburgh, had its Duquesne Zemps. By 1950

our town had eight or so Little League teams (boys 8 – 12 years old) and latter

a Pony League team (Middle School) and an American Legion team for teens after

the high school season was over.

Branch Rickey (http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Branch_Rickey, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/6d0ab8f3) , while General Manager of the St.

Louis Cardinals, pioneered the farm system in the 1920s and 30s as a means of

developing players for the future and thus built the Cardinals into a dynasty. The Cardinals had working relationships with

teams at different levels or had part or full ownership. Its scouts would discover a player, have him

sign a contract, and place him with a Class D team in a corresponding league. The players would advance up to Class C,

Class B, Class A, Double A, and Triple A before making it to a major league

team. Today we have Rookie League, A,

AA, and AAA. There are less farm teams

today, but much of the development work is done by college baseball teams. Today players are drafted out of high school

or college by major league teams and assigned to one of their farm clubs.

The marketing of

baseball was simple……..no Hat Day, Bobble

Head Day. Pup Night, Fireworks Night, Free Shirt Night, Zombie Night, or other promotion. They just played baseball. However, there was Children’s Day on Saturday

afternoons 12 or under got into the Right Field Stands for free. I saw many a game that way; my Mom didn’t

worry about me; all I had to do was hop a trolley car and it dropped off the

fans a block away. Thursday afternoon

was Ladies Day in which the women got in for something like 50 cents. The last Sunday home game was Prize Day, a Fan Appreciation Day.

If the team did well or had an exciting player or two, attendance was high. The 1948 Pirates, being a pennant contender (4th place), together with Ralph Kiner’s home runs, drew 2 million fans. The dismal 1952 team (42-112) drew about 500,000 fans.

How

would those players have done against the stars of today? We’ll never know, at least in this world. For some links to the history of the Pittsburgh Pirates with their win - loss records, click on: https://www.mlb.com/pirates/history - is the most recent and most comprehensive. http://pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/pit/history/year_by_year_results.jsp or http://pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/pit/history/, http://www.baseball-almanac.com/teams/pirates.shtml, and http://pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/pit/history/timeline.jsp. For the career statistics on anybody who ever played in the major leagues, go to www.baseball-reference.com and www.baseball-almanac.com. These same references have team standings, league leaders, and all kinds of other data going back over a hundred years. http://baseballhall.org has bios on every member of the Hall of Fame and other data. Googling almost any notable major league player will yield further results and articles. For an overall history of the Pittsburgh Pirates since its founding in the 19th Century, go to The same history, historical facts, a historical timeline, Hall of Fame members, records, all time rosters, etc. c. can also be found on the Pittsburgh Pirates website at pirates.com.

APPENDIX

Frank Thomas

Photos were added to this article

which was copied from http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ff969dc6

Some Links to Articles and Stats on

Frank Thomas

It’s surprising how many links there

are to sources of memorabilia on him.

http://www.ebay.com/sch/sis.html?_nkw=1958+FRANK+THOMAS+OF+THE+PITTSBURGH+PIRATES+Sports+Illustrated

Frank Thomas played during an era

when team owners looked upon their players as chattels. By their standards,

Frank Joseph Thomas was considered a rebel. Much of his career was spent

bickering with management over his worth to them. In his early career with the

Pittsburgh Pirates, Thomas’s adversary in such battles was the man sometimes

called “El Cheapo,” otherwise known as Wesley Branch Rickey.

During the 1950s Thomas’s demands

were considered selfish but by today’s standards they would be probably be

considered reasonable. His negotiations with Branch Rickey became legendary

around the Steel City. In 1955 Thomas was the lone holdout on a Pirates club

that was coming off a last-place finish 44 games behind the New York Giants.

Rickey could not believe that this young man would have the audacity to

challenge a $2,000 raise, from $13,000 to $15,000. The slugging outfielder

sought a salary of $25,000 after a 1954 season in which he belted 23 home runs

and drove in 94 runs with a career-high batting average of .298. On top of

that, he received 24 votes for Most Valuable Player on a team that lost 101

games.

What Thomas should have realized was

that he was dealing with the same general manager who reportedly informed

future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner, after Kiner won his seventh consecutive home

run title in 1952, “We finished in last with you, we can finish last without

you.” When Thomas held out for 17 days in 1955, he kept in shape by working out

at the University of Pittsburgh. While he did not get the $25,000 he wanted, he

did get a raise that brought his salary to $18,000. This compromise did not sit

well with Mr. Rickey.

Frank Thomas, a late-season

acquisition by the 1964 Phillies, grew up in the shadow of Forbes Field. Born

in Pittsburgh on June 11, 1929, he entered a seminary in Niagara Falls,

Ontario, as a teenager to study for the priesthood but could not shake an itch

for baseball, and he decided to forgo a career in the priesthood. Frank’s

father was Bronaslaus Tumas, a Lithuanian who had immigrated to the United

States in the early 1900s. He lost his right arm in a work accident, and was

employed as a foreman for the laundry department at Pittsburgh’s Magee Hospital.

His mother was Anna Marian Thomas, a homemaker from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. He

had three siblings – an older sister, Delores, and the younger Marie and John.1

Thomas’s professional career began

in 1948 when the Pirates signed him and sent him to Tallahassee of the Class D

Georgia-Florida League. He played in the outfield, made the league all-star

team, and led the league in RBIs with 132. He moved up to Class B Waco and Davenport

in 1949 and then Class A Charleston and Double-A New Orleans in 1950.

In 1951 the Pirates invited Thomas

to spring training for the third straight season. Eventually they returned him

to New Orleans. He was selected to play the outfield in the Southern

Association all-star game, and his play that season (.289, 23 home runs) earned

him his first late-season audition with the parent club.

Thomas made his major-league debut

on August 17, 1951, at Forbes Field against the Chicago Cubs. He started in

center field and batted third in the order. He got his first hit, an RBI double

off Paul Minner, in an 8-3 Pirates win. He was 1-for-4. On August 30 he hit his

first major-league home run, off George Spencer of the New York Giants at the

Polo Grounds in New York.

The next year Thomas went back to

New Orleans for more seasoning. His manager was Danny Murtaugh, the future

leader of two World Series-winning teams. “I guess that it was good luck in

disguise because I had one heck of a year,” Thomas said in 1990.2

He again was picked for the all-star game and led the league in homers with 35,

scored 112 runs, and collected 131 RBIs while batting .303. On August 6, 1952,

a sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Press asked why Thomas was still in

the minors, especially when the Pirates were in dire need of hitting, and

Rickey was hard-pressed to answer. Thomas was finally brought up in

mid-September, played in six games and managed two singles. Although he played

in only six games, Thomas felt that he had finally earned a spot on the team.

Thomas stayed with the Pirates in

1953. He had been paid $6,000 in New Orleans in 1952, and he requested an

additional $1,000 from the Pirates. Rickey’s response was said to be, “I can’t

pay major-league salaries to minor-league players.” Fred Haney, the Pirates’

manager, assured the youngster that he would get every opportunity to prove

himself at the big-league level. Thomas responded with 30 home runs and 102 RBIs.

Thomas became a regular after the

Pirates traded Ralph Kiner to the Cubs in June 1963. When Kiner departed, so

did Kiner's Korner – previously known as Greenberg Gardens – which had

shortened the outfield fences by 30 feet, from 365 feet to 335. Thomas later

figured that had the shorter wall remained, his home-run totals would have

doubled and most likely he would have finished his career with more than 500.

The wall was highly unpopular with the Pirates’ pitching staff. Pitcher Murry

Dickson (66-85 with the Pirates in 1949-53) once said ruefully, “With some

justification, the ‘Greenberg Gardens’ was largely responsible for my record.”3

After his successful first full

major-league season, Thomas told Rickey, “I’m a major leaguer now and want to

be paid accordingly.” Rickey asked him how much he wanted and Frank said

$15,000. This did not set well with the Mahatma, who paused, thought about it

and suggested, “You go along with my offer of $12,500 and if you have another

good year, I’ll take good care of you.”4

Against his better judgment, Thomas accepted.

In 1954 Thomas batted.298 with 23

home runs and 94 RBIs. He went to Rickey expecting a substantial increase for

1955 but was offered $15,000 and was then compared negatively with Ralph Kiner.

“If you are going to compare me, give me the same opportunity,” Thomas replied.

“Put back Greenberg Gardens for me and I’ll hit you 50 homers because I can

tattoo the scoreboard.” Thomas refused to sign Rickey’s contract and became a

holdout. Rickey warned him, “Go ahead and hold out. I’ll keep you out of

baseball for five years.”5

Thomas succeeded in getting the team’s offer up to $18,000, and he reluctantly

signed, then proceeded to have his one bad season for the Pirates: 25 home

runs, 72 RBIs, and a batting average of .245.

In 1956 Joe Brown became the

Pirates’ general manager. That season Lee Walls played a lot of left field, so

Thomas moved to third base at the request of manager Bobby Bragan. Bragan

appreciated his athleticism and remarked, “He was our long-ball man, but he was

a team player and had great hands.” Although he struggled defensively, Thomas

played in 157 games, ties included, batted .282, and had 25 home runs and 80

RBIs. Brown offered a $1,000 raise for 1956, which Thomas accepted.

In 1957 Thomas played in 151 games,

split among first base, third base, and the outfield. He enjoyed a decent

season: a .290 batting average, 23 home runs, and 89 RBIs. Brown raised his

salary to $25,000 for 1958.

Left to right Roberto Clemente, Frank Thomas,

Lee Walls and Bill Virdon in 1958 when the Pirates finally became respectable

after numerous poor years mired in 7th and last place since

1950. In June the Pirates were even in

first place on June 7 before fading and finishing in 2nd place. The year 1958 was Thomas’ best year.

The Pirates slugger was worth the

investment. He had the best year of his career in 1958, with 35 home runs and

109 RBIs. On August 16 Thomas clouted three consecutive home runs against the

Cincinnati Reds. At last he seemed happy. He enjoyed the new California venues

of Seals Stadium in San Francisco and the Los Angeles Coliseum. He especially

enjoyed the new home of the Dodgers and loved taking aim at the Coliseum’s

short left-field fence. He predicted that if he played in Los Angeles, he could

challenge Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs. Thomas started the

All-Star Game at third base and said this was his proudest accomplishment,

since the players chose the starters.

The comfortable feeling came to an

end on January 30, 1959, when the Pirates traded Thomas and three other players

to the Cincinnati Reds for catcher Smoky Burgess, pitcher Harvey Haddix, and

third baseman Don Hoak. The trade would go down as the worst in Reds’ history

and many, including Thomas, believed it was responsible for the Pirates’ World

Series championship in 1960. Before Thomas signed his contract, he informed

Reds general manager Gabe Paul that he had a bad hand that was not healing

properly. Paul was not worried; Frank asked for a salary of $40,000, which he

got. The hand really bothered him and affected his play. The pain brought tears

to his eyes whenever he applied pressure. Both of the Reds managers that year,

Mayo Smith and Fred Hutchinson, had him on the bench a lot. A doctor later

discovered that tumors were growing on the nerves of his hand. This did not

save Thomas from being traded for the second time in a year. On December 6,

1959, he was shipped to the Cubs for outfielders Lee Walls and Lou Jackson and

pitcher Bill Henry.

Manager Bobby Bragan with Frank Thomas (left) in

1957.

Thomas had surgery on his hand and

had only a fair season with the Cubs: a .238 batting average, 21 homers, and 64

RBIs in 479 at-bats. He had a couple of run-ins with manager Lou Boudreau that

left Thomas feeling that Boudreau was trying to show him up.

One time in Los Angeles, general

manager John Holland offered Thomas $1,000 if he would work with and coach the

younger players. Thomas refused, but the GM stuck the money in Thomas’s shirt

pocket. Two weeks before the end of the season, Holland gave him another

$2,000. Suspecting something, Thomas told management, “If my contract for the

coming year includes a cut in my salary, you are going to hear from me.”6

He was right; his salary was cut by $8,000. Frank wrote a ten-page letter to

Holland saying he felt the Cubs were trying to buy him off. Holland offered to

take back the $3,000 and not cut his salary, which he did. Thomas gained a

tremendous amount of respect for the GM, feeling Holland was fair and someone

whom he could talk to.

Thomas’s next stop was Milwaukee. On

May 9, 1961, as he was on the team bus heading to a game with the Braves, he

was informed that he would be switching uniforms when the team arrived. He

walked into the dressing room and was greeted by his new manager, Charlie

Dressen, who told him that he would be the regular left fielder. Thomas

performed well in a lineup with Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Joe Adcock. He

enjoyed a productive year, batted .284 and smacked 25 homers. General manager

John McHale informed Thomas he wanted him back for 1962, but in November the

Braves traded him to the brand-new New York Mets. He tried to get in touch with

McHale but the Braves GM never returned his calls. Thomas’s comment: “General

managers treated players like slaves.”7

At 33, Thomas had one of his best

offensive years for the expansion Mets in 1962, hitting 34 home runs. “We had a

veteran ballclub, with many players from winning traditions.”8

Thomas and his teammates felt that they would have a fair record. But the

pitching quality did not match the team’s hitting capability. This team lost a

record-setting (for the modern era) 120 games.

Thomas loved playing in New York.

The fans were great. They had been hungry for a National League team ever since

the Dodgers and Giants left for California after the 1957 season. Said Thomas,

“I had fun on the Mets,” a team whose fans took them into their hearts and

forgave everything. No team got more enthusiastic support. In addition to the

fan support, Casey Stengel took the media pressure off them. He entertained both

the fans and the press with his “Stengelese.”

Thomas had several power outbursts

in 1962; during one three-game stretch, he hit six home runs. Because he had

star status in New York, he hoped that he would make a lot of money in

endorsements, but his endorsement money amounted to just $2,000. In 1963, while

he was still productive, hitting .260 with 15 home runs, he got caught in a

roster squeeze as the Mets gave playing time to younger players like Ed

Kranepool. Thomas became expendable and a good target for a contending team. In

1964 such a deal occurred.

On August 7, 1964, Thomas was traded

to the Phillies for prospects Gary Kroll and Wayne Graham, and cash. It was the

first time Thomas played for a serious contender. After the trade, Philadelphia

expanded a 1½-game lead to 6½ games. On September 8 Thomas fractured his right

thumb sliding into second base. As Jim Bunning recalled, a ball was hit to the

left of Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills. Thomas faked a break for third in hopes

of distracting Wills but then had to dive back to second and broke his thumb.

He played the rest of the game and reached base twice, but then sat out the

next 16 games. By the time he returned in late September, the Phillies’

inglorious collapse was almost over. In 39 games for Philadelphia, he hit seven

home runs and batted .294.

On July 3, 1965, an incident of

pregame horseplay occurred around the batting cage between Frank and Richie

Allen before a contest with the Cincinnati Reds. Several versions of what

happened have been given. The website www.BaseballLibrary.com states that

Thomas swung a bat at Allen during a disagreement. It has been said that Thomas

used racial slurs; both would “bury the hatchet” years later. Whatever

happened, Allen belted a three-run triple in the seventh inning and Thomas hit

a pinch-hit home run to tie the score in the eighth. The Reds eventually won,

10-8. After the game the Phillies sold Thomas to the Houston Astros. He played

in 23 games for the Astros and and then was sold to the Milwaukee Braves, for

whom he played 15 games. In April 1966 he was released by the Braves (now in

Atlanta) and in May he signed with the Cubs. He played in five games with the

Cubs and 25 with their Tacoma affiliate before he was released. He retired

then, with Frank’s career totals for 16 years in the majors of 1,766 games,

1,671 hits, 286 home runs, 962 RBIs, and a batting average of .266.

Frank married the former Dolores

“Dodo” Wozniak in 1951. She died of pancreatic cancer in 2012. They had eight

children: Joanne, Patty Ann, Frank W., Peter, Maryanne, Paul, Father Mark, and

Sharon (deceased), and as of 2013, 15 grandchildren. As of early 2013, he lived

in Ross Township, Pennsylvania, just outside Pittsburgh, and spent time playing

in charity golf tournaments. He used to play in old-timer’s games in Pittsburgh

when they had them. Thomas is a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Alumni

Association and has participated in a number of fantasy baseball camps. As a

65-year-old during the 1994 All-Star festivities at Three Rivers Stadium in

Pittsburgh, he drove one deep into the gap.

He once summed up his attitude about

life: “I always felt if you gave 100 percent at whatever you did, you didn’t

have anything to be ashamed of.”9

This biography is included

in the book "The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia

Phillies" (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more

information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Finoli, David, and Bill Ranier, The

Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing

LLC, 2003).

Golenbock, Peter, Amazin’

(New York: St. Martins Press, 2002).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, The

Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd edition. (Durham, North

Carolina: Interlink Publishing, 1997).

Kuklick, Bruce. To Every Thing a

Season (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991).

O’Brien, Jim. We Had ’Em All the

Way, Bob Prince and His Pittsburgh Pirates (Pittsburgh: Geyer Printing,

1998).

O’Toole, Andrew, Branch Rickey in

Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000).

Peary, Danny. We Played the Game

(New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Thomas, Frank, Ronnie Joyner, and

Bill Bozman, Kiss It Goodbye! The Frank Thomas Story (Dunkirk, Maryland:

Pepperpot Productions, 2005).

The Baseball Encyclopedia, Eighth Edition (New York: Macmillan, 1990).

Emert, Rich. “Where Are They Now?

Frank Thomas.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (online) accessed April 17, 2003.

Frank Thomas, BaseballLibrary.com, www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/T/Thomas_Frank.stm.

Friend, Harold. Frank Thomas

interview. “The Highlander, Official E-Newsletter of Baseball Fever’s NY

Yankees Forum”, Volume 13. March 2004

Robinson, James G. “Break Up the

Mets.” BaseballLibrary.com: www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/features/flashbacks/o4_23_1962.stm.

Personal letters between Frank

Thomas and Bob Hurte, 1992-2004.

Notes

1 Frank Thomas, Ronnie Joyner, and Bill Bozman. Kiss It

Goodbye! The Frank Thomas Story (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot Productions,

2005), 1,2.

9 Rich Emert. “Where Are They Now? Frank Thomas.” Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette (online), accessed April 17, 2003.

|

Views of a Layman with a Missionary Spirit Columns by Dr. Paul R. Sebastian Professor Emeritus of Management, University of Rio Grande (Ohio)

Saturday, August 20, 2016

(174) Major League Baseball in the Old Days in Pittsburgh..........The 1940s, 1950s, and 1960

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment